“How much debt can a government afford?”

Economy

The question of how much debt is sustainable becomes relevant at the latest when interest rates increase. A look at different countries reveals clear differences in how they manage debt.

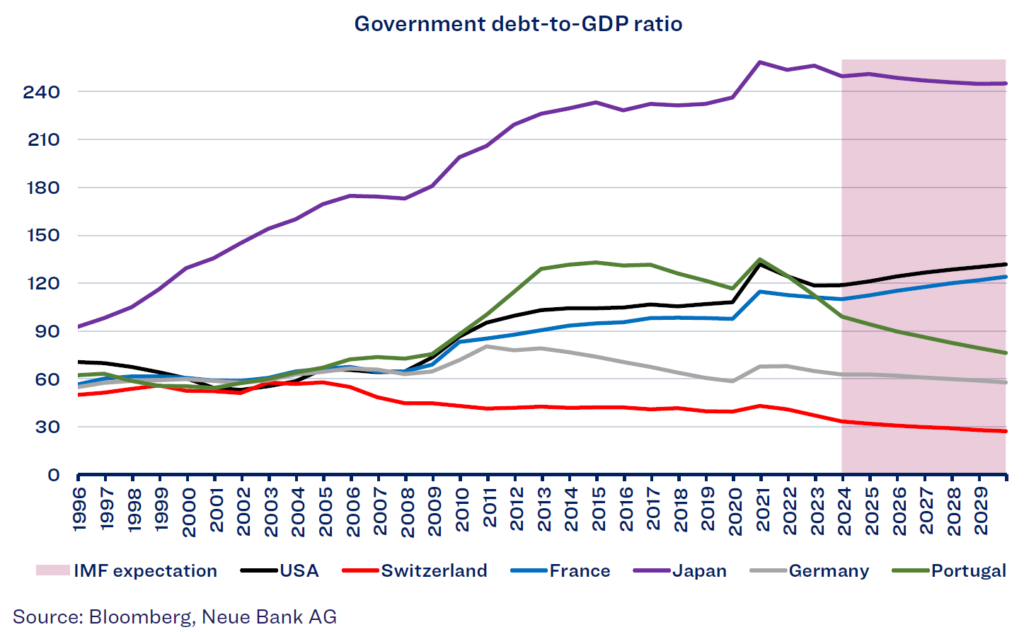

Germany and Switzerland focus on budgetary discipline through a debt brake. Portugal, once branded as one of the PIIGS countries due to its high debt levels, has recently significantly reduced its debt ratio, with the IMF expecting further improvement. In contrast, debt levels in the United States and France remain high, with no prospect of a rapid reduction. The goal is to lower the debt ratio (government debt-to-GDP) through high nominal growth rates that exceed interest costs – an approach that is politically more palatable than tax increases or spending cuts but often proves ineffective. In Japan, the debt ratio remains at a record high, with the Bank of Japan (BoJ) now holding over 50% of outstanding government bonds. Below, we outline some of the effects of relative debt levels on different asset classes.

Bonds

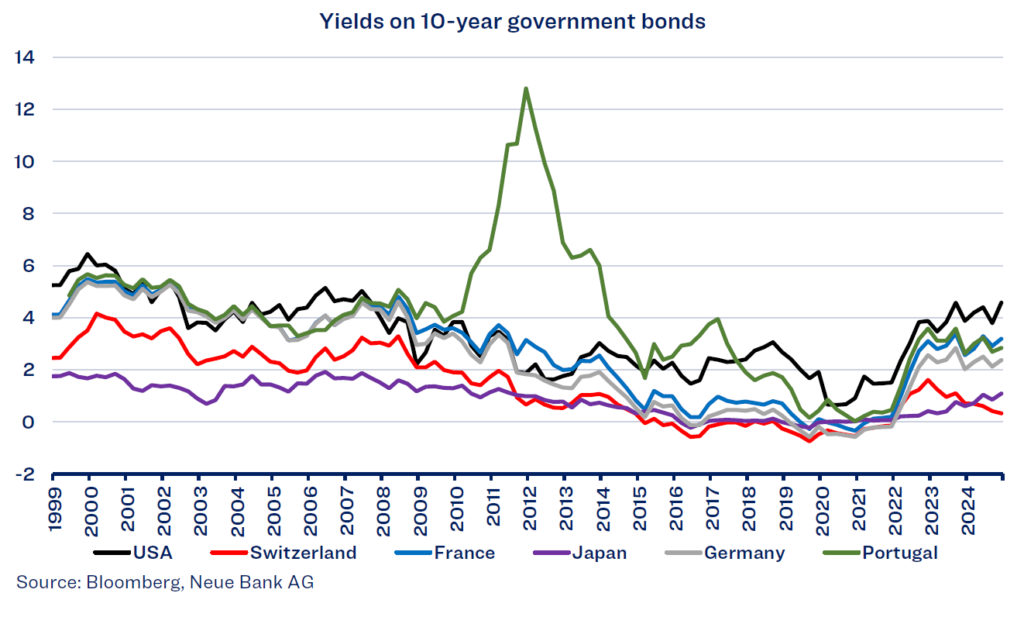

Yields on 10-year bonds rise especially when debtor quality deteriorates or inflation increases, given that lenders demand higher compensation in such cases.

The deterioration in creditworthiness is best illustrated by the development of Portugal’s bond yields. During the financial and euro crises, when the debt ratio surged from just over 70% to more than 130%, borrowing costs skyrocketed. Before the crisis, Portugal’s government paid just about the same interest rates as Germany. By the end of 2011, however, a premium of 11% was required. It was only through interventions by the European Central Bank (ECB) that borrowing costs eased again. Thanks to debt reduction and improved economic prospects, Portugal now even pays lower interest rates than France. Recently, bond yields in the United States have risen, with market observers attributing this to both persistently high inflation and growing national debt. Although the debt ratio was significantly lower at the turn of the millennium, rising interest rates at the time forced the Clinton administration to manage tax revenues more cautiously. This led to a budget surplus – a rare occurrence in the last 30 years of US fiscal policy. Switzerland, benefiting from low inflation and low debt levels, enjoys exceptionally low refinancing costs. Highly indebted Japan benefits from the ability to refinance almost entirely domestically, primarily through the Bank of Japan (BoJ), with the remainder covered by Japanese banks and trust funds. However, with inflation rising for the first time in two decades, Japan has also been forced to pay higher capital market interest rates, although 10-year yields remain below the inflation rate. To curb inflation, key interest rates were raised to 0.5% in January – the highest level since the financial crisis. Despite all of this, with high debt levels and rising refinancing costs, there is a global risk of public finances spiralling further out of control. During the financial, euro, and coronavirus crises, central bank interventions helped stabilise the markets.

Currencies

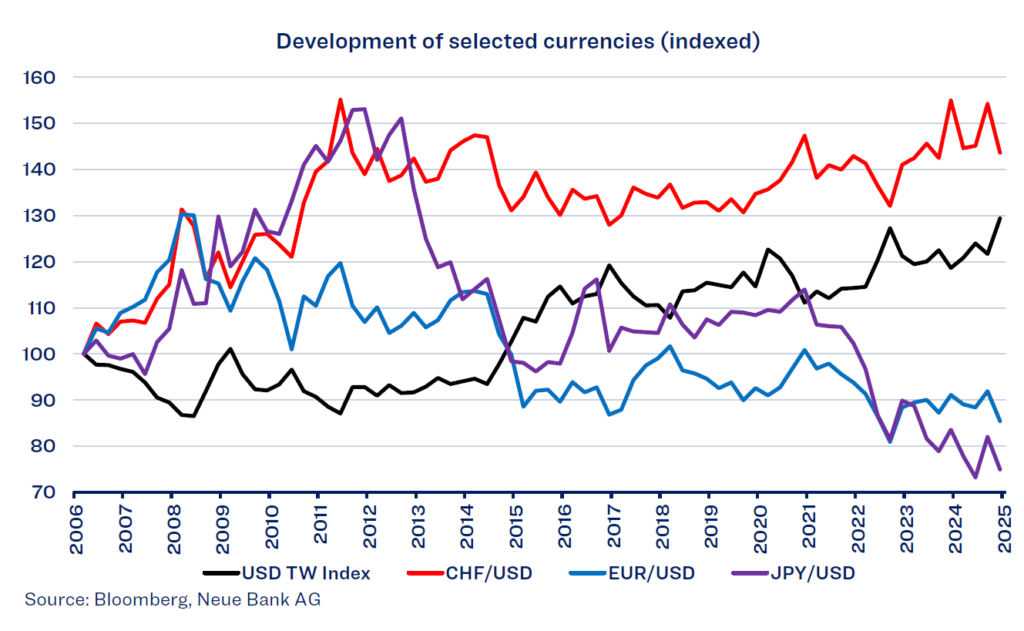

Japan’s financial sector emerged largely unscathed from the 2008 – 2009 financial crisis, with the JPY appreciating against the USD during this period. When Japan slipped into recession, however, the government introduced a stimulus programme that increased the debt ratio. Once the euro crisis was resolved following the financial crisis, the JPY subsequently lost half its value against the USD. This depreciation was driven by low interest rates, maintained through the BoJ’s government bond purchases, and an expansionary monetary policy that encouraged

borrowing in JPY to fund more profitable investments elsewhere (carry trade). The Japanese export sector benefited from this, as lower production costs improved its competitiveness against foreign rivals. However, this currency depreciation could lead to tensions with the US, given that the Trump administration views such moves unfavourably. Punitive tariffs have become a favourite tool of the US government to counter what it sees as unfair competitive advantages.

Alongside the JPY, the EUR has also depreciated against the USD since the financial crisis. Only the CHF strengthened against the greenback, becoming particularly sought after during the financial crisis and the subsequent euro crisis. The Swiss National Bank reacted by temporarily introducing a minimum exchange rate of 1.20 EUR/CHF to support the export industry. Overall, however, maintaining competitiveness remains a challenge for the manufacturing sector in the CHF currency area due to the strength of the home currency.

Equities

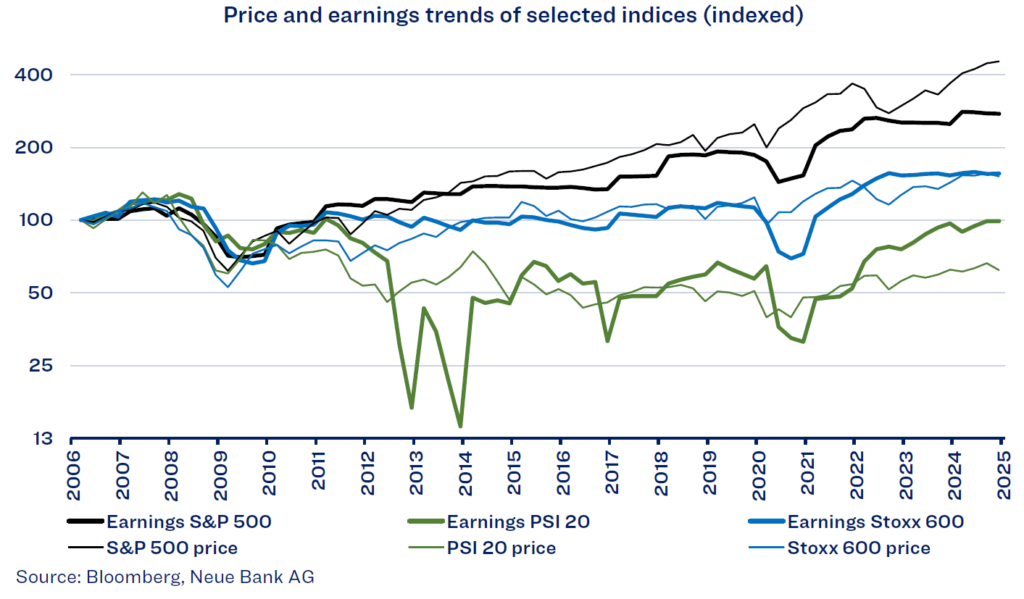

Can high levels of debt impact the equity markets as well? Looking at Portugal during the euro crisis, the answer is clearly yes. Both earnings and share prices plummeted during this period, and it took a considerable

amount of time for conditions to stabilise again. While earnings have now returned to pre-financial crisis levels, share prices continue to lag behind. Portugal is a relatively small economy by international standards, and the PSI-20 index comprises only 20 stocks. Its sector composition differs significantly from that of the European Stoxx 600 or the US S&P 500, making direct comparisons difficult.

US companies, in particular, have long surpassed their pre-financial crisis price levels, driven by the strength of the technology sector. However, unlike in Europe, share prices have outpaced earnings growth, resulting in a substantial valuation of US stocks.

Alternative investments

Conclusion: There is no general answer to the question posed at the outset. Ultimately, it depends not only on central banks but also on the confidence of market participants. How can investors protect themselves

against the risks entailed by the rising debt levels of many major economies?

Investing in gold remains a

popular alternative.

Many BRICS countries and their allies are increasingly diversifying their reserves into gold while significantly reducing their holdings of US government bonds. Supported in part by these purchases, gold recently traded at over USD 2,800 per ounce, marking a new all-time high. Inflation protection and resilience in times of crisis are frequently cited as key advantages of gold investments. However, gold remains subject to price fluctuations and does not generate income. We do not maintain a strategic gold allocation, given that the optimal distribution varies significantly depending on individual circumstances. We therefore advise our clients to hold their own appropriate allocation in a separate portfolio outside an asset management mandate. Our advisors are happy to explore possible options.

Downloads